The other day, an MMM reader stopped by and left the following comment on one of my older posts about the principles of FIRE:

I wasn’t smart enough to find FI when I was young so I sometimes feel like a lot of their advice is not going to help me or others who don’t already own a home and don’t have six- figure salaries in this post-pandemic world.

A lot of the ideas given to young folks are “house hack” “buy a fixer upper” but that is still out of reach and/or complex to navigate with current prices and interest rates. Most townships around me do not want you to chop a house up into ADU’s or multiple units. My cousin owns 60 acres of land but he is not allowed to live on a trailer on that land.

I don’t know what the next generation of FI bloggers will offer, perhaps they are already out there and I just don’t know who they are, but I’d like to hear from them.”

–

As with every critique of our ideas, I thought about this comment for a while. Tried to determine if there were any Principles of Mustachianism that were genuinely going obsolete, versus the more common side effects of Complainypants and/or Excuse-itis, two afflictions which have been weighing down our critics since the beginning.

After all, this isn’t the first time FIRE has gone obsolete. Over my retirement I’ve seen it:

- written off as just a phenomenon of the lucky winners of the 2000 Tech Boom

- declared obsolete after the 2009 Financial Crisis

- dismissed as a temporary fluke of the spectacular stock market of the 2010s

- and explained away as a Covid-era side effect that came from the taste of freedom that people got from remote work.

So what’s the situation right now?

Our commenter focuses on two things: the solid salaries of tech workers, and the major increases in house prices (and interest rates) in the most recent four years.

The first one — high salaries in general – is still a factor and I don’t expect that to change. Some jobs just pay more than others, and there’s a lot you can do to increase your income and switch jobs, and I’m all for it. However, ever-increasing income is not my usual focus here on MMM, because I have seen first hand that most people can waste almost any amount of income and still have very little to show for it.

In fact, the very existence of software engineers and doctors and other high earners who are my age and still feeling financial stress is proof of this: it’s mathematically impossible to earn so much for almost 30 years and not have an absolute shit-ton saved, unless you are also spending an absolute shit-ton of money the whole time.

So instead, we focus on how to streamline your spending and live joyfully and efficiently without compromise. We focus on reducing waste, while maintaining or even increasing all of the other benefits that come from spending money more purposefully. These skills are essential even for the highest earners, but they become even more valuable as you move down the income ladder.

So now for the second issue: housing. Does the state of housing here in 2024 screw up the whole FIRE plan?

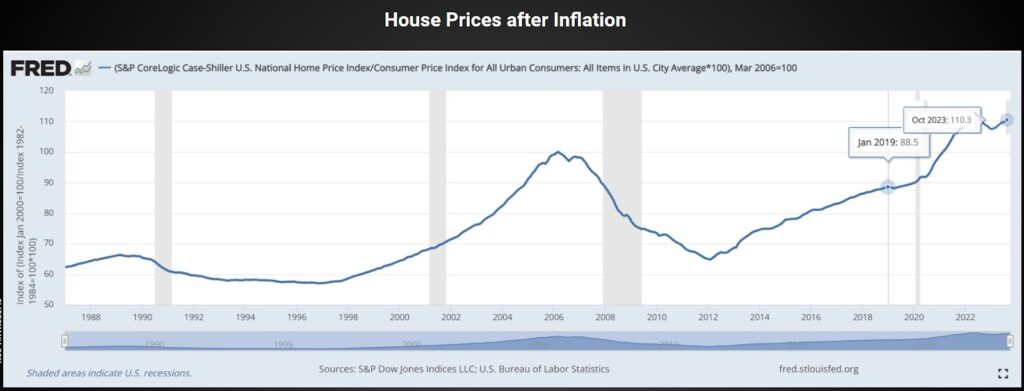

As with any question, let’s start by looking at the data: how much have US house prices actually risen – adjusted for inflation – since 2019?

It turns out that our own St. Louis Fed makes this extremely useful information available here.

So there’s our answer: houses “feel” about 25% more expensive right now than they did at the start of 2019 relative to the average salary and the price of everything else. Although interestingly enough, they are only up about 10% since the last peak in early 2006, a full eighteen years ago! So housing is a blow, but not a FIRE-extinguishing one.

However, this nationwide data masks some much bigger increases in certain popular cities, including my own: Plain old Longmont Colorado now sports a hilariously high $540,000 median home price. So houses are about triple the price they were when I started writing in 2011, which means they’ve risen much faster than the average salary. Which means houses are much further out of reach for the average person in my area.

House Shopping With Your Middle Finger

The solution to this is the same as most other problems: to stop thinking in the way our culture likes to train us (as a victim of outside forces beyond our control) and go back to thinking like a Mustachian.

Houses are just like any other manufactured product, and as such they come at a wide variety of prices, subject to supply and demand.

And just because you happen to live in a certain place (even if you were born and raised there), doesn’t mean you’ll automatically be able to afford to buy a house there. Just as a baby born upon the Apple campus in Cupertino today doesn’t automatically get a new iPhone Pro Max every year.

With every purchasing decision, you need to go through the same series of choices:

- Can I afford this thing right now?

- Do I need/want it enough to buy it?

- Are there any alternatives to meeting those same needs, and what are their pros and cons?

- What’s the best way to procure it, after considering all the points above?

So when it comes to houses, you run the numbers, then decide between renting or buying or house hacking. You might start by doing the analysis right in your own city, but also keep in mind that there are lots of other cities and even countries in the world, and there are happy people living in all of them.

But Wait: I don’t want to move to a whole new place!

At this point, people get defensive. We all have ties to our current location, and the stronger the ties the more difficult it becomes to consider moving.

But there’s a difference between genuine, positive bonds to a place and just plain old fear of change. So it’s my job to at least make you question your assumptions, because not doing so is what got you where you are, and it’s also what got our country where it is.

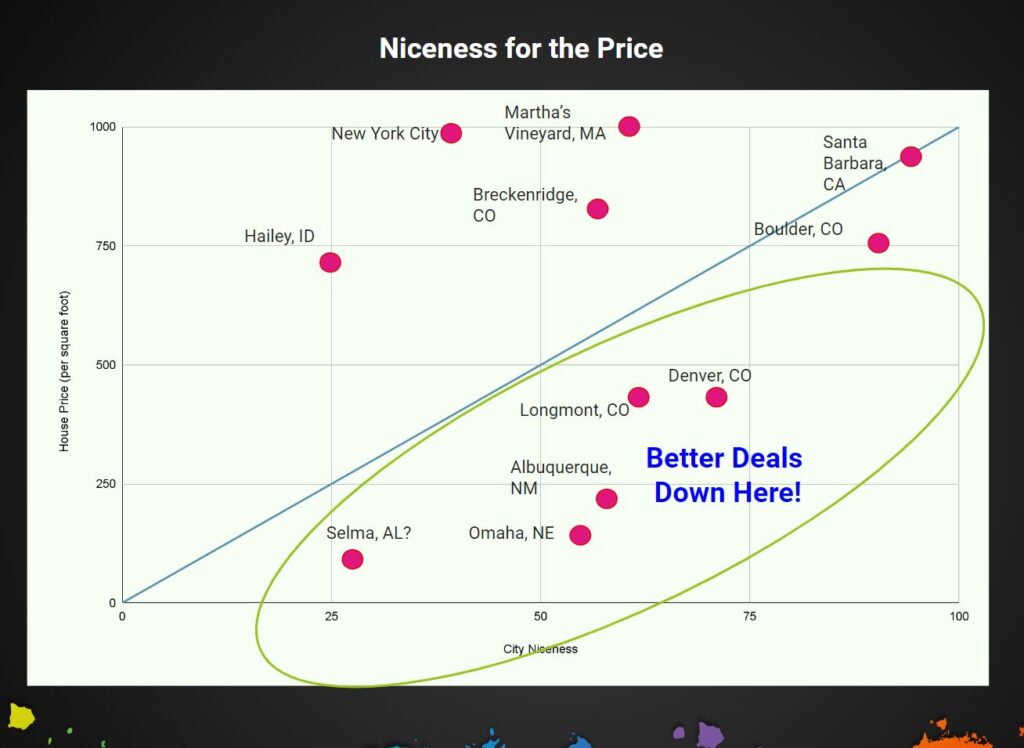

And on a country-wide basis, I notice that our general fear of relocating creates a very irrational pattern of house prices. They are ridiculously high in some places and ridiculously cheap in others. There does seem to be a general correlation between niceness and cost, but not a perfect one (especially since everyone has their own definition of “nice”)

And that’s where the opportunity lies.

Example:

I moved to Longmont in 2005 because it met our young family’s needs at the time, at the right price with homes about $200,000. Today, at the $540,000 price level (houses average about $450 per interior square foot) it has to compete with a much broader range of cities which offer nicer amenities at equal or lower prices.

Let’s do a hypothetical search using another amazing tool: FRED’s list of the top 1000 metro areas with price per square foot, and plot some of them based on my own judgment of their desirability:

I’m biased towards Colorado because I have so many ties there, and I also highly prioritize sunny climates. My chart suggests that if I wanted to save money, I might start looking around in Albuquerque, whereas Denver would give me a nicer life in the same price range as my current city of Longmont. And if I were willing to spend even more on housing to live somewhere even nicer, I should suck it up and move to Boulder.

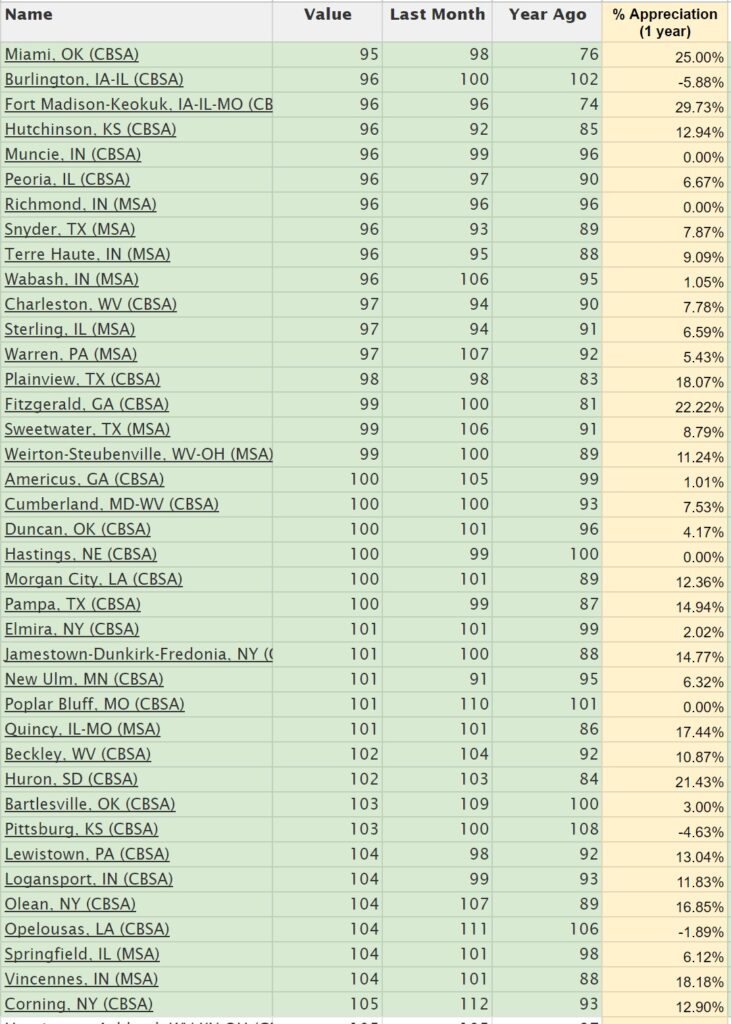

Just for fun, I pulled the data from that same FRED website into a separate google spreadsheet (which I’ll share here) and sorted it by cost per square foot. Then, I highlighted a band of affordable cities with housing centered on the $100 per square foot range, which would mean a 2,000 square foot house is about $200k.

As an added bonus, I added a column to calculate the change in house prices over the past year, just in case it helps us see if a city is on the way up or getting cheaper at the moment.

A chart like this is just a starting point – you’d need to read more about any place and then go visit in person before considering a move. But the idea is to start with data, and then do some fun research based on what you learn.

The Earth Awaits: Casting a Worldwide Net

House prices are a valuable metric, because they influence the cost of living more than almost anything else for the typical Mustachian. After all, biking and nature are always close to free, Costcos are available nationwide, and we probably care less than average about the costs of other services like valets and salons.

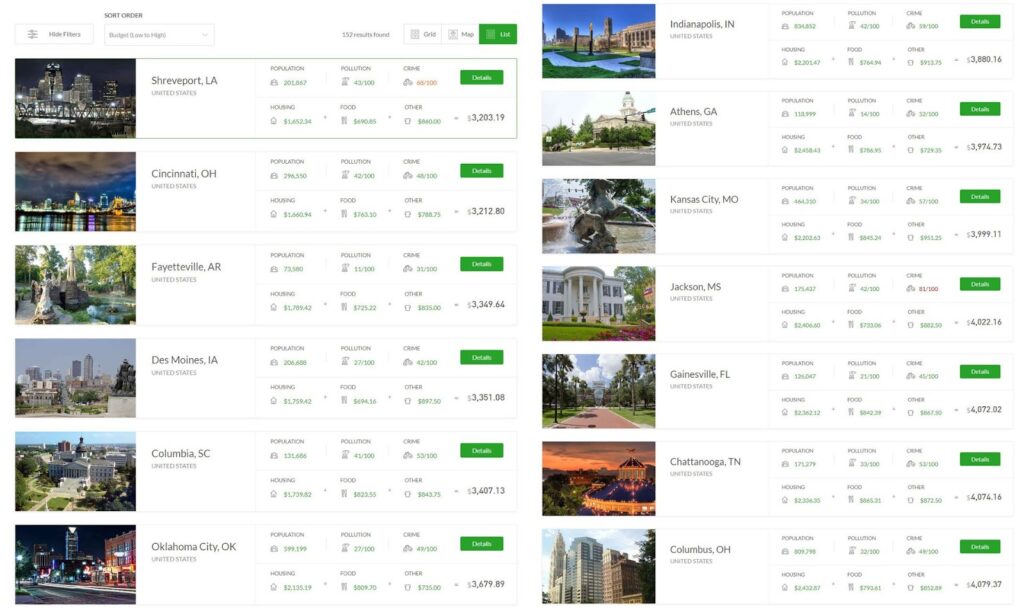

But there’s still plenty of value in looking at the bigger picture, considering more data points, and also being open to renting versus buying your housing. For this, I’m a big fan of a FIRE blogger-created site called The Earth Awaits, and we can take it for a test drive right now with the following search criteria:

Geographic area: North America

My total monthly budget: $0-$6000

Family size: 2

Apartment type: Two bedroom (outside city center)

Temperature range: January lows not colder than 10F

The exact parameters don’t matter too much, as long as you don’t make them too narrow. The important thing is the resulting list, which is meant to give you ideas to research further. For example, that first simple search gave me this list:

Hey, that’s interesting. I like how the site shows the population right on the main list, because that provides a big clue to the “feel” of a city. I personally like the feel of a 50k-200k person town, so I might look into Fayetteville, Columbia or Athens. I’ve also been to Chattanooga and really like that place – who knew it was only about as expensive as Columbus Ohio?

So Should I Move?

In the end, your physical environment – the people, access to nature, urban features and the weather patterns – is probably the most important factor to get right in creating a happy life. The cost of living there is only one of the factors, and definitely not the most important one.

But if you choose carefully, you can probably slide yourself in the right direction along that “Nice for the Price” scale in order to get more from your life. Even if it just means making a move within your own city to live along a walking path, a little closer to work or to the people or places you care about most.

The key is just to remember that housing is like almost everything in life: It’s a choice that you get to make, and there are great rewards for putting some solid thought and effort into that choice.

Another Fun Example: Doing the Analysis on Tempe/Phoenix Arizona vs Denver

This is a fun exercise, because I’m currently living in the Phoenix area (more on that here) that is way different than the Denver metro area where I normally live. We can start with the rough measure of housing cost per square foot across each region:

Phoenix: $272

Denver: $299

In other words, pretty close. Denver metro* is about 10% higher on average, but the variations from one neighborhood to another within any major city are much larger than that anyway.

So the other factors are more important. Both are surrounded by beautiful mountain recreation and get lots of sunshine, but the climates are famously quite different. Denver is more compact but Phoenix has nicer towns in the foothills around the outskirts. In the end it’s just personal preference in weighting these various factors, and right now I kind of like the idea of both (Phoenix in winter but Colorado for the other three seasons)

More Adventurous: Let’s Try This in South America!

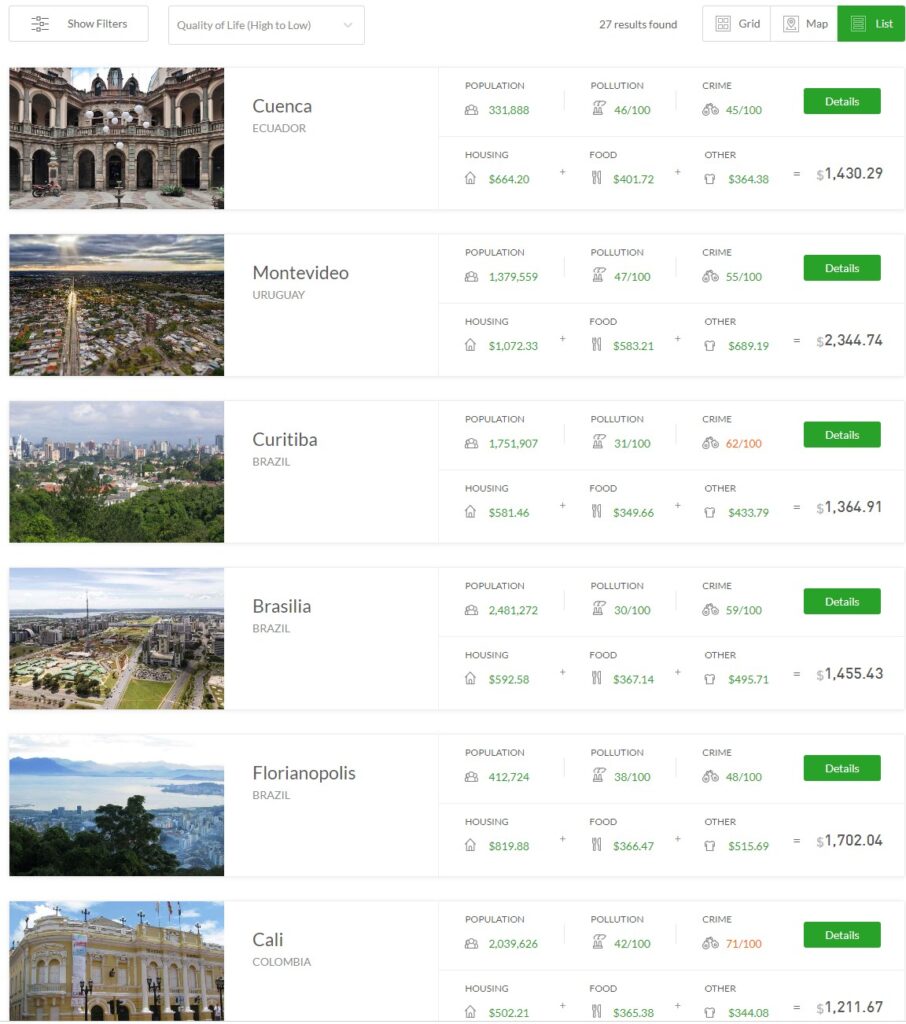

Going back to The Earth Awaits, if we repeat our earlier search but in South America, we get results like these:

Many of these spots have nice writeups if you click the “Details” button, and if anything sounds right for you, you can go on to learn much more.

It’s true that moving to a new country comes with all sorts of new learning experiences: citizenship and passports, laws and traditions and driver licenses, and of course having to cross an international border every time you want to return to your home country to visit family.

But guess what? If this stuff sounds daunting to you, it’s probably a sign that you need to do it more.

At its core, moving to a new place – even internationally – is just a series of relatively easy Adulting Puzzles. You type stuff into your computer, read the resulting stuff that pops up on your screen, and make the occasional phone call and visit to an official office. I had to do all the same stuff when moving from Canada to the US, alone and just six years out of high school myself.

Sure, it can feel like a “hassle” if you think of it the wrong way, but you know what’s a way, way bigger hassle? Living in a not-very-good place for life, or working an extra 15 years just to afford the higher cost of living in your current city, because you’re too scared to do a few weeks of work to make a big move to a better place.

If a rules-and-paperwork-hater like me can do it, almost anyone can.

Your Turn:

While we covered a few examples of actual places in this article, the real purpose was to explain the thought process behind deciding when and where to move. And there are many of you out there besides me who can do the same thing, but better. And we’d love to hear from you!

If you have some favorite cities and countries for good living, or useful techniques for scoping them out, please share them in the comments. I strongly believe that the more we help each other find the right place and enjoy the planet more thoroughly and more efficiently, the better off we’ll all be. So let’s get moving.

—–

* Denver metro on the Fed site includes all the suburbs rather than just the core city which is much smaller and more expensive, but the same is true for the nicer parts of Phoenix so I figure it’s a fair comparison)