Too Much in 401(k) and Tax-Deferred Accounts?

Before the article, check out the latest on my podcast, Personal Finance for Long-Term Investors:

Now, here’s today’s article:

Niki wrote in and asked:

For the last several years, I’ve been able to save $80,000 pretax dollars (401k) per year as a business owner. But now I’m worried my pre-tax bucket is getting too large.

I might have opportunities for Roth conversions later, but I’m wondering if it would be worthwhile to pay some tax now and save some of that money in a brokerage account.

Because brokerage accounts are taxed at capital gains rates, doesn’t it make more sense? There’s some complicated math here that I may not be seeing, so any insight into this would be helpful!

This is an interesting and common question.

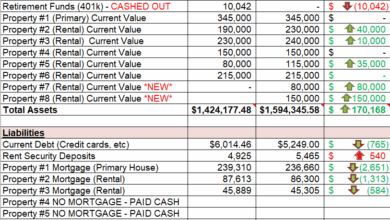

401(k) accounts are ubiquitous. Between their large annual maximums, employer-matches, and the past ~15 years of bull market stock growth, it’s common to see large 401k balances.

But is there such a thing as “too big” a pre-tax bucket?

Definitely.

Let’s dig into the details.

Fixing the Premise

First, I want to clarify part of Niki’s question. She wrote:

“Because brokerage accounts are taxed at capital gains rates, doesn’t it make more sense?”

The money going into a brokerage account is first taxed as income. Then, any growth in the account will then be taxed at capital gains rates. And any dividends and interest along the way are also taxed on an annual basis (some as income, some at capital gains rates).

There are three possible layers of tax. All else equal, you will pay more tax on the dollars in a taxable brokerage account than on the dollars in qualified accounts (401k, IRA, etc).

The article below shares some similar comparisons. It’s difficult to conceive a scenario where a taxable brokerage has better tax outcomes than a qualified account:

But It Still Might Be Worth It

Sure, it’s unlikely the taxable brokerage will ever provide better tax advantages. That’s ok.

Taxable brokerage accounts offer the critical, hard-to-quantify benefits of flexibility and liquidity.

I think it’s fine to sacrifice some tax advantage as a trade-off for more flexibility. One reasonable example:

Niki is currently contributing $80K per year into her Solo 401k. Perhaps she could dial that down, choosing to “only” contribute $50K per year into the Solo 401k.

The other $30K goes to Niki as income. Of that, ~$8K will be paid as income tax. Niki could take the remaining $22K and invest it in a taxable brokerage.

She’s still saving a lot of money, though not quite as much as before. But now, approximately 1/3 of her savings are flexible and liquid.

One problem, though? I’ve been totally subjective so far. Why’d we split $80K into 50K + 30K (minus taxes)?

Can we be a bit more rigorous and objective here?

Objective Reasons to Choose Taxable Over Tax-Deferred?

Let’s dig into some legitimate, objective reasons to limit contributions to tax-deferred accounts, and begin more contributions to taxable accounts.

Everything is Traditional/Tax-Deferred.

Pretty simple here. If your current retirement buckets are ~100% Traditional, you should plan to eventually begin contributing to Roth and taxable accounts. Perhaps “eventually” is right now.

For most people, Roth contributions make more sense than taxable contributions. Roth should come first. But, specifically facing the issue of “flexibility,” Roth assets suffer many of the same problems as Traditional assets. Taxable accounts provide the most flexibility!

How much? What do the numbers look like? Opinions vary, and everyone’s individual scenario will align differently with income tax brackets and capital gain brackets.

One rule of thumb I’ve heard? Aim for [Roth + Taxable] to be 25% or more of your retirement assets.

Future RMDs Too High!

If you use your current Traditional account balance, add in more contributions over time, and assume reasonable growth rates, what do you expect your future RMDs to be? More precisely – what do you expect the tax rate on those future RMDs to be?

Your current marginal income tax rate may be lower than the future RMD tax rate. That’s a flashing red light; slow your Traditional contributions and diversify your tax buckets.

Just pay the tax now. Then use those dollars to fill up Roth and/or taxable accounts.

Liquidity / Cash Flow Concerns – Especially in Early Retirement Years

If you’re retiring before traditional retirement age (e.g. “FIRE” movement), you’ll definitely need a taxable brokerage account.

But even if you’re planning a “normal” age retirement, it’s valuable to have a flexible brokerage account with “only” capital gains taxes attached to withdrawals.

I realize you can get early access to retirement accounts (e.g. via rule of 55 and SEPP/72[t]), but even those access routes are rigid in their application.

A taxable brokerage has no rigidity.

Managing ACA Subsidies and Other Corner Cases

Retirement is full of corner case concerns.

For example, many early retirees use the ACA for their healthcare, and ACA premium subsidies (a.k.a. government money to make their healthcare cheaper) are currently based on income. Having various retirement buckets (tax-deferred Traditional, tax-free Roth, and taxable) can make ACA planning much easier.

An Easy Decision Tree – Do You Need More Taxable Dollars?

For a simple starting point, I would take the following five steps to determine if you need more taxable dollars in your long-term portfolio.

Step 1: Project your future RMDs and their associated tax rates.

Step 2: Compare the result from Step 1 against your current income tax rates

Step 3: Assess your current taxable bucket size as a percentage of overall long-term dollars

Step 4: Take a “best guess” at what your “early years” of retirement will look like, and whether you’ll have an additional need for flexible dollars (e.g. you have FIRE plans)

Step 5: Based on Steps 1-4, shift new long-term contributions accordingly – possibly away from tax-deferred, toward taxable.

Thank you for reading! Here are three quick notes for you:

First – If you enjoyed this article, join 1000’s of subscribers who read Jesse’s free weekly email, where he send you links to the smartest financial content I find online every week. 100% free, unsubscribe anytime.

Second – Jesse’s podcast “Personal Finance for Long-Term Investors” has grown ~10x over the past couple years, now helping ~10,000 people per month. Tune in and check it out.

Last – Jesse works full-time for a fiduciary wealth management firm in Upstate NY. Jesse and his colleagues help families solve the expensive problems he writes and podcasts about. Schedule a free call with Jesse to see if you’re a good fit for his practice.

We’ll talk to you soon!